20 Years Ago: John Lennon’s FBI File Is Revealed

When John Lennon decided to settle in New York City in 1971, his song “Give Peace a Chance” was well-known to U.S. authorities.

Approximately a quarter-million people sang it at an anti-Vietnam War demonstration two years earlier. The FBI believed Lennon was planning to tour the nation to promote his left-leaning politics. With the agency’s boss, J. Edgar Hoover, reaching the height of his control, and paranoid president Richard Nixon determined to secure a second term, few people in high places wanted to give Lennon a chance.

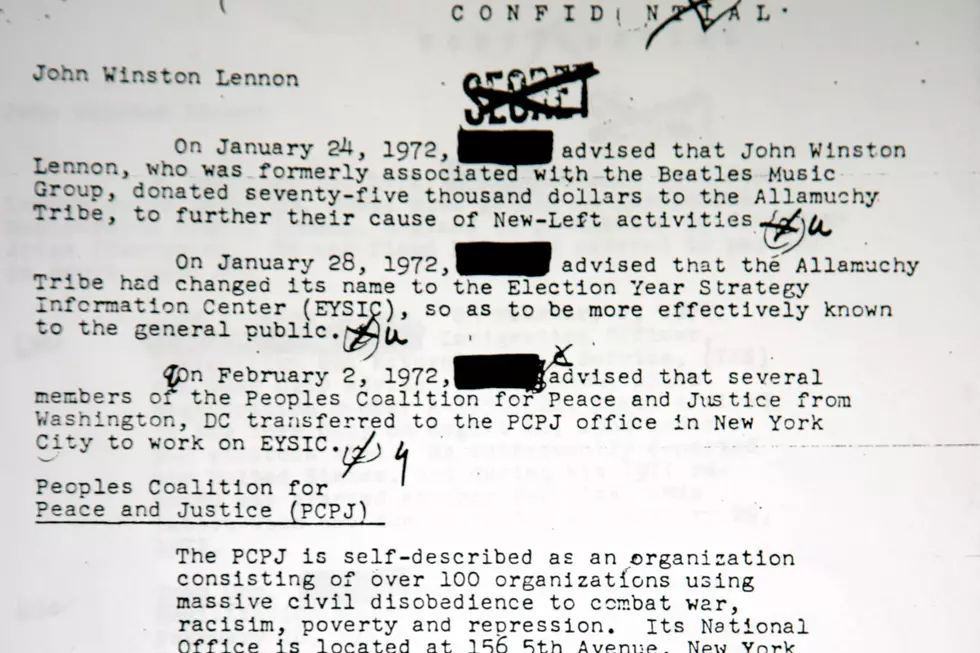

Over the coming years, the FBI gathered more than 300 pieces of intelligence about the former Beatle. The file opened with a report about his appearance at an anti-war gathering in Michigan in 1971. “Source advised Lennon prior to rally composed song entitled 'John Sinclair,' which song Lennon sang at the rally,” the operative reported. “Source advised this song was composed by Lennon especially for this event.”

The operative did not add that the “source” had received the information because Lennon had announced that the song, about a man jailed for selling two joints to a cop, had just been written.

Listen to John Lennon's 'John Sinclair'

That’s the quality of most of the “intelligence” in Lennon’s file, but it took professor Jon Wiener nearly 20 years to bring it to public attention. The FBI locked the documents, claiming the information held within them constituted a threat to U.S. security. Instead, when Wiener published his book Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files in February 2000, he was able to argue that, in pursuing the artists, the agency behaved more like the Keystone Cops.

Wiener started his campaign to publicize the documents in 1981, launching a Freedom of Information Act bid to have them revealed. When the first papers were grudgingly shared, they were redacted to the point of being pointless. As he continued his campaign, and finally got to see most – but not all – of the file in 1997, he was astonished by the “immense triviality of a lot of the information gathered.” (Many are now available on Wiener’s website.)

One report, regarded as a threat to national security, explained how Lennon met a girl named Linda who owned a parrot. The animal, said an FBI operative, “interjects ‘Right on!’ whenever the conversation gets rousing.”

Another document showed that the lyrics to “John Sinclair” were classified as confidential, even though they appeared in full on the sleeve of Lennon’s 1972 album Some Time in New York City. The FBI summarized that the song “probably will become a million seller … but it is lacking Lennon’s usual standards.” At one point, they circulated a picture of Lennon, only to realize that it was actually a completely different person who happened to have long hair, a beard and glasses.

Another note, added in 1972, contained quotes Lennon gave during a well-known interview with Red Mole magazine, and concluded that his words “can reasonably be expected to … lead to foreign diplomatic, economic and military retaliation against the United States.”

This document – but not the interview itself – remained secret until 2006, when the last 10 papers were finally released. Another of the last batch, kept secret since 1981, reported that Lennon was involved in “left-wing activities in Britain.” Wiener observed in 2000, “It's hard to believe how much effort they put into this.”

Still, authorities believed that Lennon posed a real threat to Nixon, Republicans and the government, and were able to cite some concrete examples. For one, he donated $40,000 to cover the costs of a demonstration outside a Republican convention. He also gave $75,000 to an organization encouraging young people to register and vote, and was noted to have paid the fines of people arrested during anti-war, anti-capitalist and anti-racist campaigns.

That's why they continued to pursue attempts to have him sent home to the U.K., despite warnings from senior Republicans that the move might play into his hands. “If Lennon’s visa is terminated … caution must be taken with regard to the possible alienation of the so-called 18-year-old vote,” one said.

Lennon had access to powerful lawyers and refused to give up. But the three-year battle to stay in the States came at a greater cost. “He lost his artistic vision and energy, his relationship with Yoko [Ono] disintegrated, and he gave up his radical politics,” Wiener wrote in 1984. “In this period, Lennon became a defeated activist, an artist in decline, an aging superstar.”

The authorities scored a victory: Nixon was reelected in a record landslide, but the Watergate scandal (which included some people who were active in pursuing Lennon) soon ended his presidency. Hoover died, leaving a legacy of abuse of power the FBI took years to clear. But the U.S. got out of Vietnam and continued to pursue policies that provided more racial equality than in the past.

And Lennon returned, after hearing the B-52's' “Rock Lobster” in 1979 -- a song that featured a scream inspired by Ono’s vocal delivery. “John heard it at some club in the Bahamas, and the story goes that he calls up Yoko and says, ‘Get the ax out – they’re ready for us again!’” B-52's guitarist Keith Strickland said in the book Origins of a Song: 202 True Inspirations Behind the World's Greatest Lyrics. “Yoko has said that she and John were listening to us in the weeks before he died.”

Watch John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band Perform 'Give Peace a Chance'

Soon after Gimme Some Truth was published in 2000, some media outlets reported that a file held by Britain’s MI5 noted that Lennon had “funded terrorists and Trotskyists.” Wiener countered by saying that none of the outlets considered whether the claims were true, and, even if they were, nothing illegal was ever reported.

He also confirmed that the MI5 file, which is now public, was one the FBI was still withholding; it was finally released six years later. “Instead of legitimate national security issues, these pages … document an abuse of power by the government, engaged in illegitimate surveillance of dissidents engaged in lawful political activities,” Wiener wrote. “Why is Lennon in the headlines after all these years? He personified the dreams of the ‘60s. ‘Imagine no more countries,’ he sang. … The battles of the ‘60s are not over.”

“We came here to show and to say to all of you that apathy isn't it, that we can do something," Lennon said at the 1971 protest concert. "Okay, so flower power didn't work. So what. We start again.”

The Best Song from Every John Lennon Album

More From 97X